Women, a Personal Gaze - Writing from Within

Saturday, 18.02.06

Sunday, 04.06.06

More info:

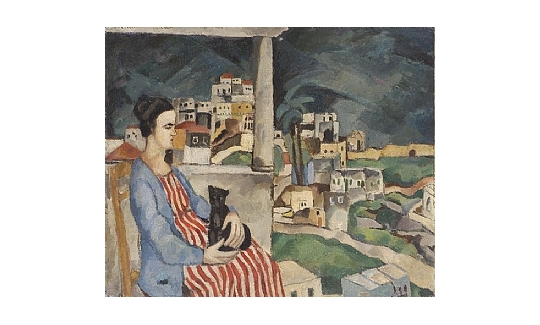

04-6030800When I was asked to select works from the Haifa Museum of Art collection for a personal exhibition, I was happy to embark on the adventure; it was yet another chance to return to my "biological city," where I was born and where I spent my formative years. I left Haifa when I was twenty, but Haifa has never left me. Time and again I find myself writing about it, missing the views of Mt. Carmel and the sea, the smell of the pine trees, and the human landscape. I have also always loved visual art, even though I have never formally studied it; I often visit exhibitions in Israel and abroad, and wander around museums not as a connoisseur, but as a huntress of colors and emotions, of excitement and thrills.

My point of departure was in front of the computer in the Museum's relatively small archive office. I went over most of the collection, which includes some 7,000 works - slide after slide marked by serial numbers, without the artists' names - a "much-more-than-you-can-eat" feast. I sought the images that would make me hold my breath because of their embodiment of human power, vitality, and beauty - a notion which in recent, postmodern times has gone somewhat out of vogue. I looked for a connection among the works that attracted me, and was not entirely surprised to find that my theme was female figures.

Women fascinate me as subject matter in my writing - their journey through life and their relation to time, which sculpts their faces, bodies and souls like water sculpts a rock; the female body's movement in space, its inherent capacity for pleasure, its cyclical nature, the life it generates; their relationships with those closest to them - partners, children, parents; their ties with other women - role models, friends, daughters; their powers, their emotional depth, their ability to laugh, hurt, change, create, be introspective. I write about "them" in the third person plural, as an onlooker, although I extract most of the experiences and insights from myself, writing them "from within." Perhaps this is why the works I selected for this exhibition are not mere "objects" for me, but also reflections - an expression of images and archetypes that I carry within me. I hope my selection is not merely subjective, and that many women as well as men will be able to find in these works - as in all good art - an echo of their own souls.

My journey naturally begins with youth, with Eugen Spiro's Figure (Woman) - a young European woman with delicate, sweet facial features, well-dressed and clearly at ease with her body. Her upright posture, her turned back, and her confident grasp of the pole, which resembles an oar, do not burden her, despite her unnatural position. She seems warm and comfortable in her clothes, which evince a measure of coquetry -especially the hat and the angle at which she wears it. To me, this is the image of a young woman who trusts herself and the world with youthful naïveté, and who rows - or rather, is beginning to row - in the river of life.

The Portrait of Mrs. Helge Schaeffer, painted by Adolphe Milich, captivated me in a particular way: the solemn face leaning sideways with apparent skepticism; the sharp, chiseled features with a hint of tenderness and sensuality in the lower lip; the penetrating eyes that seem to see right through you, the viewer, preventing you from regarding her as a mere object of your gaze; the asymmetrical hairstyle attesting to an unusual personality; the gray dress, which likewise conveys a certain gravity, covering a discernibly strong body; the broad shoulders, the exposed arms which are soft yet not vulnerable. Her seated pose is self-enclosed, unyielding; the right hand holds a wide open, feminine, romantic rose; it is ostensibly opposed to the austere figure, yet the way in which it is held leaves no room for doubt - the flower is pointed at you like a knife.

Erich Wolfsfeld's drypoint etching Mother and Child presents a non-stereotypical image of motherhood. The mother and child's gazes are invisible, their eyes are shut and they are not smiling. It is a private moment not intended for an outsider's gaze. The mother's face is fully concentrated on the kiss, as if her life depended on it, sucking vitality from the baby's plump cheek. The infant's expression is somewhat tormented, as if his vitality is being sucked away. Wolfsfeld revealed a hidden truth about motherhood, or about parenting more generally: we feed on our children just as much as we feed them. The raging lines further enhance the lack of harmony in this image.

Abraham Walkowitz's three drawings are part of a series numbering dozens, possibly even hundreds, of works in which he commemorated Isadora Duncan - the legendary American dancer whose pioneering work championed free, natural movement, and was performed with flowing tunic-like costumes and bare feet. Walkowitz created expressive, movement-filled portraits that highlighted the interplay of body and fabric in the work of an innovative, creative female artist.

As part of this exhibition, I selected three female nudes. Hermann Struck's Female Bust aroused my interest due to the shadow on the wall - the dark, hidden side of the naked, exposed young woman. Eliyahu Gat's Nude depicts a light-colored, ripe, whole, self-contained nude. The woman's head rests serenely on her arm, her face is turned toward a blue rectangle - possibly a window, possibly a painting in the artist's studio - the colors are bright and optimistic. By contrast, Ira Moskowitz's Torso portrays a corpulent elderly woman, her arms crossed behind her back, surrendering to the artist's sober gaze with a measure of defiance: This is me, here is my face, here is my body, you can read in them, as on a map, the life I have lived. I regret nothing and I am ashamed of nothing.

Agnes Lazar's Untitled conveys a somber mood. The small figure, curled up in horror, is not the image of a specific woman, but of a human creature vanquished by overpowering, dark forces - a disaster, physical or mental illness, dejection, or a profound fear of death. The feet strive to escape; the head seeks a hiding place. Even those who have never experienced such emotions can imagine their impact, as in a nightmare made real.

Moshe Gat's Grandmother of the Artist reminded me of members of my own family: the eyes that have already seen it all - wells of sorrow and wisdom behind spectacles; the face crisscrossed with wrinkles and the furrow, caused by worry, between the brows; the lips closed tight to prevent the pain from escaping; the body, no longer reveling in its womanhood, in a black attire, a widowed body; the hands gnarled by years of hard work. This is a portrait of an archetypal grandmother.

At the conclusion of this journey is Käthe Kollwitz's expressionist engraving, Death and Woman - the violent, premature demise of a woman whose strong young body fights death, in its traditional representation as a skeleton, while a little child desperately clings to her breast.

Several works in the exhibition - including two silkscreens of figures in urban landscapes - depict women seen from a male perspective. One of these works, Uri Lifshitz's Dizengoff, depicts a Tel Aviv woman from her waist down; her shapely legs and stiletto heals, are an object for the man's gaze, which expands until it unfolds underneath her like a catwalk. A German shepherd raising its leg to urinate appears on the right, reinforcing the ironic effect. Is the artist's gaze indeed sexist, or is it critically examining the sexism characteristic of Israeli men? Yoshida Katsuro's Work no. 9, on the other hand, depicts a young Japanese woman in a mini dress, seen from behind as if caught in a play of doubles: the front of her body is her persona, the image she projects, an object for the gazes of those approaching her face on; her double, glimpsed from behind, is the subject - the experiencing, observing consciousness hidden behind the persona.

Salvador Dali's wife, Gala, served as an inspiration for the color lithograph depicting the mythological image of Medusa's head. Dali's impressive Medusa, in expanding watercolor stains, appears to be drowning. Her hair is not made of snakes, and she appears more human and tormented than scary and monstrous.

Finally, two images injected with a humorous streak: Moshe Hoffman's Woman Exercising and Herman Berserik's Bread and Sewing Machine. I chose to include Berserik's painting in the exhibition even though it is not a human portrait, since it is derived from a female sphere of meanings and associations. It reminds me of my mother, who used to sew her own dresses from Burda magazine patterns, and of the Israeli "dressmaker" institution - women who until the 1970s used to sew by commission, at home or in the customer's home. It reminds me in particular of sewing lessons in school, when my foot used to get confused while pushing the pedal, so that the machine, to my great horror, would start running wild. Berserik painted a sewing machine which is a metaphor for wild, rebellious, capricious femininity, a machine with a life all its own.

List of Works