Joshua Sobol

June 24, 2006 - October 29, 2006

I once used to paint. That was many years ago, when I was a boy and understood little about myself. My painting teacher Shlomo Katz, a new immigrant from Sweden, arrived in our small village and painted the surrounding citrus groves. I studied his oil paintings, which were made on plywood and Masonite panels, and for the first time I saw how many shades of gray there were in the cypress trees described to us as green, and in the sky we were told was blue. When I looked at the grays painted by Shlomo Katz, I was astonished to discover they contained entire realms of color: a warm gray whose grayness contained glimmers of ochre and brown and blood-red, and cool grays under which simmered shades of ultramarine and Prussian blue and lemon yellow, and even a pink whose pallid red drowned in light-hued cream.

When I learned how to mix paints, I understood that color is something that hides something that hides something. It seems to me that already back then I realized that color is a dramatic event frozen in time, and that observing it brings this drama to life in the soul of the beholder. Shlomo Katz dedicated many hours in the course of his painting classes to observing the world around us: potatoes and onions, pine trunks and eucalyptus trees, the darkling groves on the outskirts of the village and the burnt sky crumbling into the dunes. The climactic moment came when we began seeing the air surrounding the objects. We were then ordered to shut our eyes and paint what we saw in our imagination; only then were we allowed to reopen our eyes and paint the memory of what we had imagined. If the memory grew dim, we were asked to shut our eyes once again and wait for it to reappear and come into focus before returning to our paints and canvases.

It is perhaps thanks to this experiential form of learning that I began to understand that color does not unfold in space like form, nor in time like music; rather, it unfolds entirely within the soul - that is in memory, in the imagination and in the will, in boldness and in the recoil from it, in passion and renunciation. I thus also came to understand that the closest things to color were smell and taste - our most intimate senses, which invoke the most inward events in our soul with great power. The proximity of color to taste and smell explains why color circumvents logic and acts directly upon the soul.

When I was given the opportunity to exhibit my personal choices from the collection of the Haifa Museum of Art, I was thankful for the opportunity to search for and discover, among the thousands of paintings in the collection, those I would have been happy to have painted myself. And so I set out to find the paintings that would appear to me vividly when I shut my eyes, after having first observed them with open eyes.

I close my eyes and see Zvi Meirowitch's painting Sun over the Desert - a desert landscape wallowing in the blood of a slit-throat sun that flares, with the power of a hydrogen bomb, in the elusive moment between the life that is still with us in all its intensity, and its vanishing in another instant as if it had never existed. Meirowitch's fiery flow of blood contains flashes of gray, which will be planted in his disaster-filled landscape once the flames subside. Within the terrible heat one may already feel the chilling presence of death, since Meirowitch's blood-red is already pervaded by a gray vapor that will soon overtake it from within, just like a line of dialogue in a play is imbued with the power of the subtext folded within it like a fetus in its mother's womb.

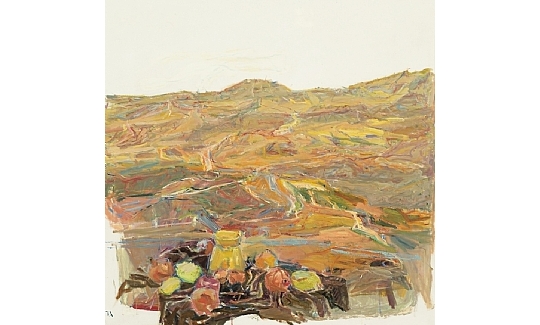

And once this intense heat cools somewhat, Eliyahu Gat's Tavor landscape (In front of Tavor Mountain) emerges from it like a skinned hunk of flesh surrounding a tangle of gnarled muscles and a mass of white tendons connected by a network of red arteries and bluish veins. This hunk of flesh, the earth, is thrust against a gray, metallic, cold and lifeless sky.

The same battle between subsiding heat and growing cold is powerfully expressed in Moshe Kupferman's work Painting. The gray masses grow black around the blues, which in turn swallow the fiery pink tongue as it gradually turns gray.

The house in Michael Gross's painting House in a Landscape is a tiny, ephemeral presence, whose heartbreaking solitude appears against an endless expanse of summer earth colored an intense bronze, and a steel-gray sky that stretches across the horizon. The monumental power of the natural elements hardly leaves any room for human existence, so that its signs appear like a torrid mirage, an intermittent and phantasmagorical fata morgana.

The plot of land depicted in Avraham's Eilat's work Untitled may appear like a magnetic field or stretch of savanna grass. Above the gray earth, which obeys some mysterious power that sweeps anything that is carried to it or grows in it in the same direction, there extends another, dark field, heavy and dense with hues of gray. The upper field is overtaken by a storm of contradictory forces that catapult it into a chaotic whirlpool threatening to crush the lower, light-gray field, which is ruled by an intentional order. Within the big picture is a small picture that distances the gaze; like a camera lens that zooms out, it reveals to us that from afar the stormy and chaotic field looks quieter and more orderly, almost like the lower field. Above, in the picture within the picture, there extends once again a gray, metallic sky, devoid of any signs of life.

Yehezkel Streichman's painting Untitled transported me back to the painting classes in which we began to observe the air surrounding the objects. During these classes we discovered that air is like a screen or sometimes several layers of screens through which objects glimmer. I remember my painting teacher taking us outside and turning our attention to the faraway mountains barely visible in the east; pulsating as they evaporated in the scalding summer heat, they appeared vaguely like unraveled threads seen through screens of gray, dusty air.

This is all that is left of the village or city in Aviva Uri's drawingLandscape: ethereal outlines of houses melting and disappearing into an ocean of rusty, gray-brown air, beyond which one cannot distinguish between earth and sky.

And the essence of everything described thus far is encapsulated in Abraham Raphael 's sculpture Landscape: the earth covered with torn branches or remnants of summer thistles, or broken and desiccated swamp plants, or perhaps a metallic representation of those same power fields visible in Avraham Eilat's painting; and beneath this field there extends another field, whose vertically arranged components are being pulled towards an invisible center down below; and above this vertical, "earthy" field there extends a third field whose tassels are pushed or pulled upwards by another power, which enables them to stand upright until their strength is finally extinguished and they collapse and break, falling and becoming part of the outspread field of their predecessors, who similarly broke when their strength ran out.

And how can one do without Nahum Gutman and his gray Haifa Port, a gray filled with echoes of different shades that unites the sea and sky into one monolithic expanse; within this colorful grayness there appear several stains of color designating ephemeral objects, a ship and flags waving in the wind, here today and gone tomorrow; and once they are swallowed and disappear, there will remain only the eternally gray atmosphere above the land.

Yet beyond all these words, I chose works I can observe in my imagination when I shut my eyes after having seen them with open eyes - works that seem to have created previously nonexistent connections between the nerve synapses in my brain; and when I shut my eyes I see and feel through these images the land I saw, understood and felt when I faced it as a child; once I became a man and put an end to the affairs of childhood, I no longer saw or felt this land other than in a vague manner, beyond many screens. Then along came these art works and restored to me that great loss that is called love.