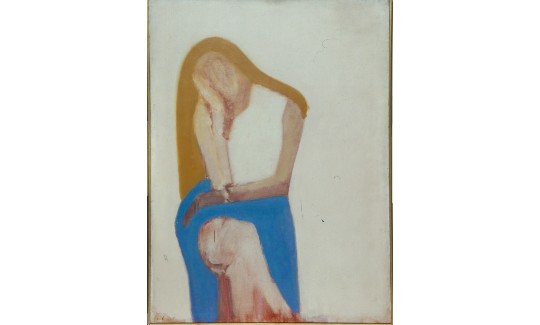

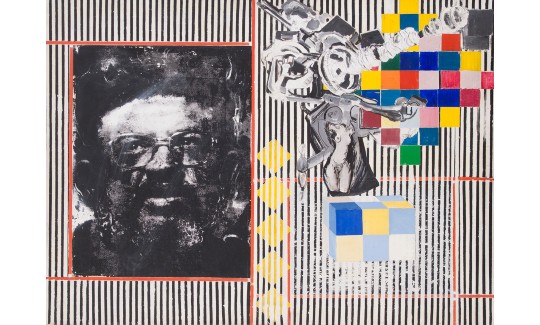

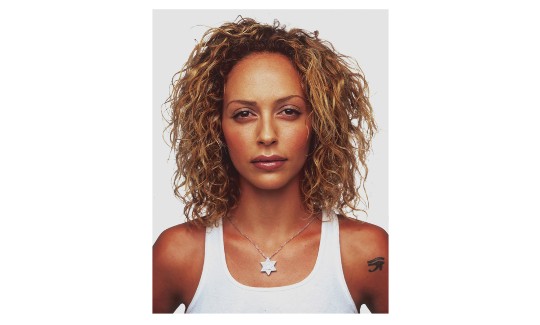

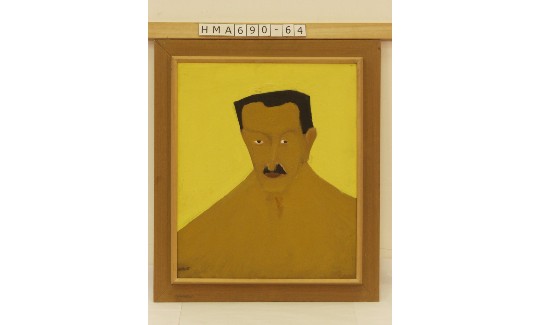

This hall features social portraits. These are portraits because they depict individuals, unique human phenomena of singular DNA, feelings, and thoughts. At the same time, they are also class portraits; portraits of the life circumstances forced on the portrayed people, which ascribed them to specific social and economic class categories. Many of the works focus on people from underprivileged classes, proudly presenting figures who are easily ignored, to shed light on the challenging conditions they confronted, and restore them with a human dignity and unique qualities.

The point of departure for the choice of works in this hall was Social Realism. The Social Realists believed that art plays a social role, and sought to promote socialist ideas in their work, in contrast to the abstract trend prevalent in Israel in the 1950s, which was inspired by the art centers in the capitalist West. Abstract painting sought to detach itself from visible reality, whereas the Social Realists adhered to reality, especially its intricate aspects. The Social Realists—among them Gershon Knispel, Naftali Bezem, Moshe Gat, and Ruth Schloss—portrayed human figures and focused on themes which the followers of abstract eliminated from the canvas, issues that the nascent Israel itself had difficulty confronting: the absorption of immigrants from North African and Middle Eastern countries, destroyed Palestinian villages, austerity, and unemployment. This artistic trend was prevalent mainly among kibbutz members, and took root in one city in Israel: Red Haifa.